In these first few months of 2025, this blog has been exploring a counterintuitive dynamic: poverty in the midst of plenty. I don’t mean this in the sense of wild wealth inequality, or not only that. Mostly, I’m curious about the great cheapening of everything.

Because there is a lot of everything! And the more of everything there is, the less valuable it all becomes. Among the glut of content, there’s exceedingly little art, anything that feels new or exciting or worthwhile. Maybe politics has reached a high tide as well, with lines drawn and crossed with equal zeal by partisans fighting for scraps discarded by billionaires. Meanwhile, liberalism lies exhausted, welcoming in the fascists with an extended hand. This all might be described as stasis, both the stagnation that comes when we can’t identify what’s precious to us anymore and the strife that doomed ancient cities in Greece.

This week I want to look at a similar dynamic taking place on the streets. Protests during the first Trump term broke turnout records, and yet their aims were constantly frustrated.1 Maybe you and I crossed paths at one of those giant rallies from 2017 to 2020: #NotMyPresident demonstrations outside Trump Tower, the Women’s March on the National Mall, the climate strikes led by Greta Thunberg, the uprisings in the wake of George Floyd’s murder. Now Trump is again our president, a rogue Supreme Court has stripped women of the federal right to their own bodies, and 2024 was both the warmest year on record and the deadliest for victims of police violence. Huge protests, little change. Poverty in the midst of plenty.

I am not naive. No one with any exposure to politics believes that there’s a straight causal relationship between “big protest” and “big policy change.” And yet — the institutions of America’s 20th-century social democracy are hollowed out. How can the media, civil society groups, and political parties, those entities that enjoy more direct power over big policy change, feel so brittle and yet remain solid enough to hold back these waves of protest?

Two preliminary answers:

One set of institutions has been transformed by popular revolt. It’s just on the right. Trump humiliated the mainstream GOP establishment in 2016, won over Fox News’ business interests in his first term, and bulldozed his way past the Koch Brothers’ protestations. I don’t think it’s a stretch to call Trump the culmination of the conservative movement’s 50-year assault on labor law and civil rights. This victory is all the more impressive considering the end of Roe, one of its crowning achievements, occurred during a Democrat’s tenure in the White House.

Strategy — the pathway to winning a goal based on a clear-eyed assessment of actually existing conditions — has become a lost art, replaced by a well-worn playbook of left-coded activities that no longer correspond to a successful mode of politics. It’s…tactical fetishism.

First, the fetish. Marx used “fetishism” to critique the quasi-religious stature that economists endow the laws of supply and demand. The commodity fetish is the peculiar attribute that animates the consumption economy: flatscreen TVs are worth this amount, strawberries during winter time are worth that amount, and five dollar bills are worth five dollars. There is nothing inherent about these values — the objects are given worth by social relations that could, conceivably, price the TV below the strawberries — but we treat them as inherent, resulting in their fetishistic quality. This is, I think, where alienation comes in: the value becomes independent of the work the laborer puts in to produce the commodity in the first place.

Now, the tactic. Big giant marches were a calling card of the #Resistance era. The best example of turning this tactic into a fetish occurred with Erica Chenoweth’s “3.5% rule.” Popularized during a 2013 Ted Talk, the rule states that “no government has withstood a challenge of 3.5% of their population mobilized against it during a peak event.” It’s based off some cool research. Assessing historical data across 323 protest movements from 1900 to 2006, Chenoweth and co-author Maria J. Stephan claim that nonviolent resistance was twice as effective as armed rebellion at removing dictators from power. Early on in Trump’s first term, their 2011 book Why Civil Resistance Works was cited by journalists, organizers, and posters as a potential guide for how, as one headline put it, “Trump could be forced out of office.”

But then, in April 2020, Chenoweth published a paper including some “cautionary updates” about how the rule has been applied by social movements. The political scientist reminded readers that the rule should be interpreted as a “tendency” and not a law.2 But as at least one other scholar has pointed out, the goal of activating 3.5% of a populace to induce policy change became, erroneously, the north star of some protest movements.

The clearest example of a coordinated effort to mobilize that 3.5% is not the #Resistance to Trump but Extinction Rebellion in Europe. The climate group made the number central to its theory of change, with the UK faction going so far as to launch “Project 3.5.” I don’t know if they have reached that threshold across the pond. But in the United States, despite record breaking turnout at the Women’s March in 2017 and the summer of uprisings in 2020, the #Resistance never came close.3

But failure to mobilize 3.5% of the population during a single protest is not why Trump is back in office and climate change is worsening. Big protests do not have mystical powers. They should not be worshipped as a fetish, but organized from as a starting point.4

In this I agree with Zeynep Tufekci’s observation that a giant protest used to function as a signal of organizational capacity and discipline, but in the age of social media, that signal is far more inchoate. The March on Washington in 1963 took more than a year to plan. It was one peak of an escalating campaign to win federal civil rights legislation. The 2017 Women’s March, in contrast, came together in a matter of weeks. Tufekci put it well in an interview in 2018: “The threat is, look, if we can do this, think what else we can do, right? So that’s why I think the easier a protest is to do, the less power it signals.”

Protest needs to signal power to win. Tactical fetishes, from the viral Instagram post (whither the 24-hour economic boycott?) to the choreography of arrests in blue cities, do not.

Strategy breaks the fetish. Putting the tactic in context of current conditions and a campaign plan helps organizers answer key questions: What do we want? What are we trying to do? Is this the best way to do it? It may even lead to some tactical innovation — something, at last, new that responds to the conditions we find ourselves in. I’ve always loved the story of the threatened “shit-in” at Chicago’s O’Hare airport for both its novelty and its strategic genius.

The script is stale. But it’s ours. We have the power to revise it.

Burn After Reading

I’ve been enjoying

reflections on organizing in this moment over at . This blog post was partially inspired by his discussion of the #50501 rallies last month. I encourage everyone to read it:If anything became clearer after 90 minutes of this pep rally, it was this: At most, 50501 is a hashtag movement that has invented a new symbol and has the wherewithal to do a few things like aggregate reports of protests on a common page (which is still under construction). It’s not the unified, muscular opposition movement people have been looking for; it’s a feed.

A note on method

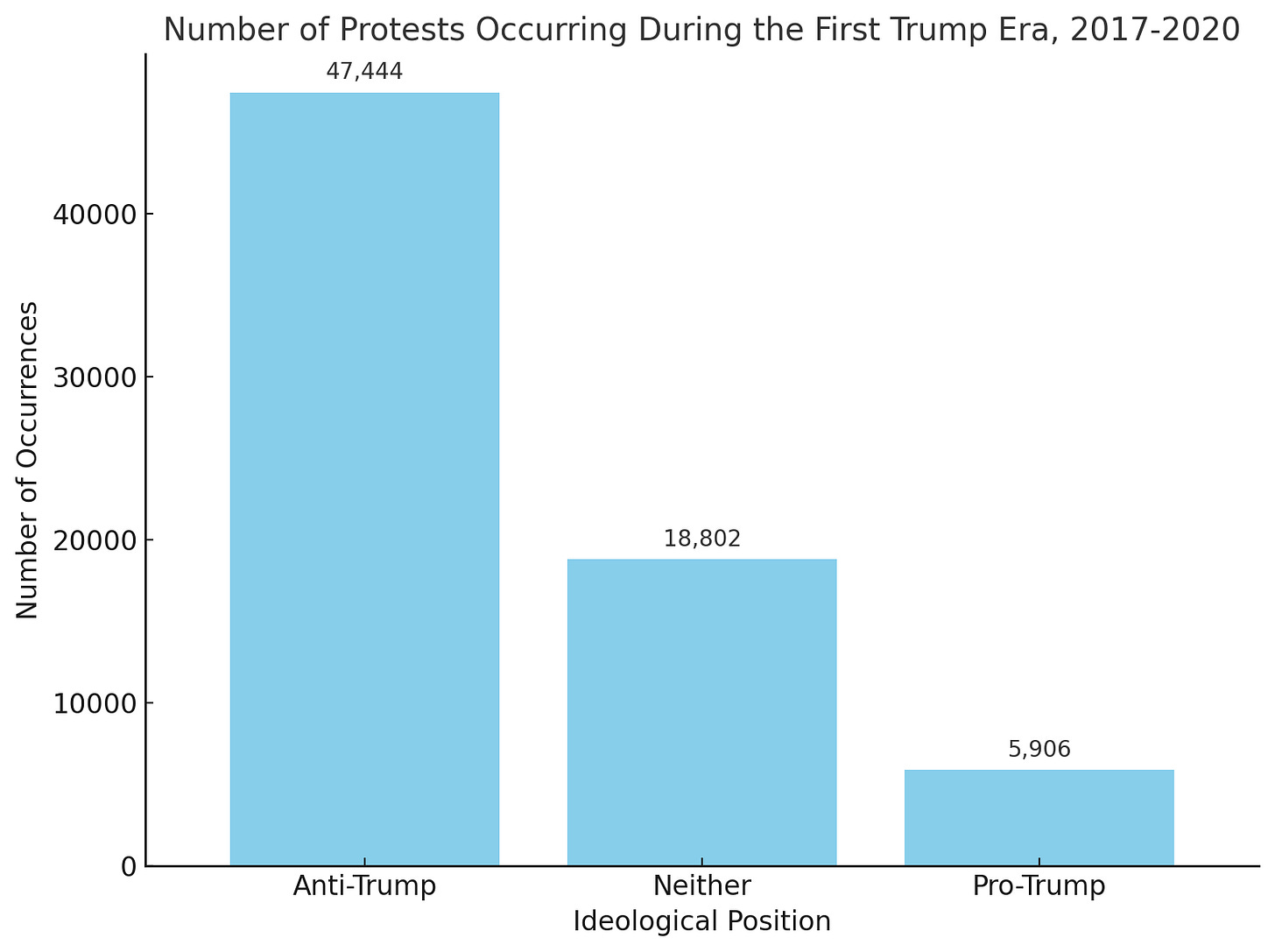

The data in the table in this post come from the Crowd Counting Consortium, an effort that Chenoweth started in 2017 to estimate the size of the crowds that the Women’s March drew. From January 2017 to December 2020, roughly equal to Trump’s first term in office, the Consortium identified 72,181 unique, in-person protest events: 47,444 were anti-Trump, 5,906 were pro-Trump, and 18,802 had no clear position.

The vast majority of the anti-Trump protests for which we have data were relatively small – fewer than 1,000 participants each. There were 208 protests with more than 10,000 protestors, only one of which, however, researchers estimate breached one million participants: the New York City Pride march in June 2018, which was more than twice the size of the next biggest single-day protest, the Women’s March in DC in January 2017.

The majority of the ten biggest protests took place on just two days: January 21st, 2017, the day of the first Women’s March after Trump’s inauguration, and June 24th, 2018, a day of queer celebration during Pride Month.

Though as Mark and Paul Engler point out, the success of protest movements is not only measured in narrow policy outcomes but also in energizing wide swathes of the public to pursue goals of their own. Calling a protest a “failure” is often self-serving, anyway, a way for those in power to diminish challenges to their rule.

There’s even a newly identified exception: a 1962 revolt in Brunei, where 4,000 people, constituting 4% of the country’s population, launched a failed revolution.

See the “note on method” for where these figures come from.

It’s not for nothing that Sunrise, before our formal launch, recruited for early members at the People’s Climate March in DC in April 2017.

Republicans are nothing if not fetishes!