Let me get this out of the way: I think Joe Biden is an enormously flawed candidate who should step aside to allow a leader with a better chance of defeating Trump lead the top of the Democratic ticket in November.

I’m just skeptical that’s going to happen. My purpose here is to explore why, using the currency of politics: power.

There is of course the characterological explanation for Joe’s recalcitrance — being cowed out of the presidential race in 1988 amidst a plagiarism scandal, choosing not to run in 2016 and allowing a weaker candidate to lose to Trump, a shocking come-from-behind victory in the 2020 primary after losing miserably in Iowa and New Hampshire, and building an entire political identity around being a scrappy underdog who has overcome hardship and tragedy to win the highest office in the land.

Understanding the psychological incentives of a decision-maker is essential to forcing them to move. This is because campaigners have two major paths to victory: 1) change the risk / reward calculus for the target, which involves getting inside their head (“know your enemy,” if you will) or 2) eradicating the target’s legitimacy and support to force their hand. The best campaigns do a mix of both.

Let’s bracket Biden’s psychological profile for now to focus on factors more within the public’s control. I want to talk about structure and power.

Political parties in general, and the Democratic Party in particular, are factious coalitions filled with competing interests, ideologies, principles, and egos. Political scientists Daniel Schlozman and Sam Rosenfeld have an excellent new book that surveys the rise and fall of American political parties and the machines that drove them. The core thesis of the book is that the contemporary party structure has been hollowed out by the reforms of the era of mass politics.

To the extent that there is a party line in 2024, then, it comes from the party leader — Joe Biden. No one is going to force him to step down. He has to come to the decision himself.

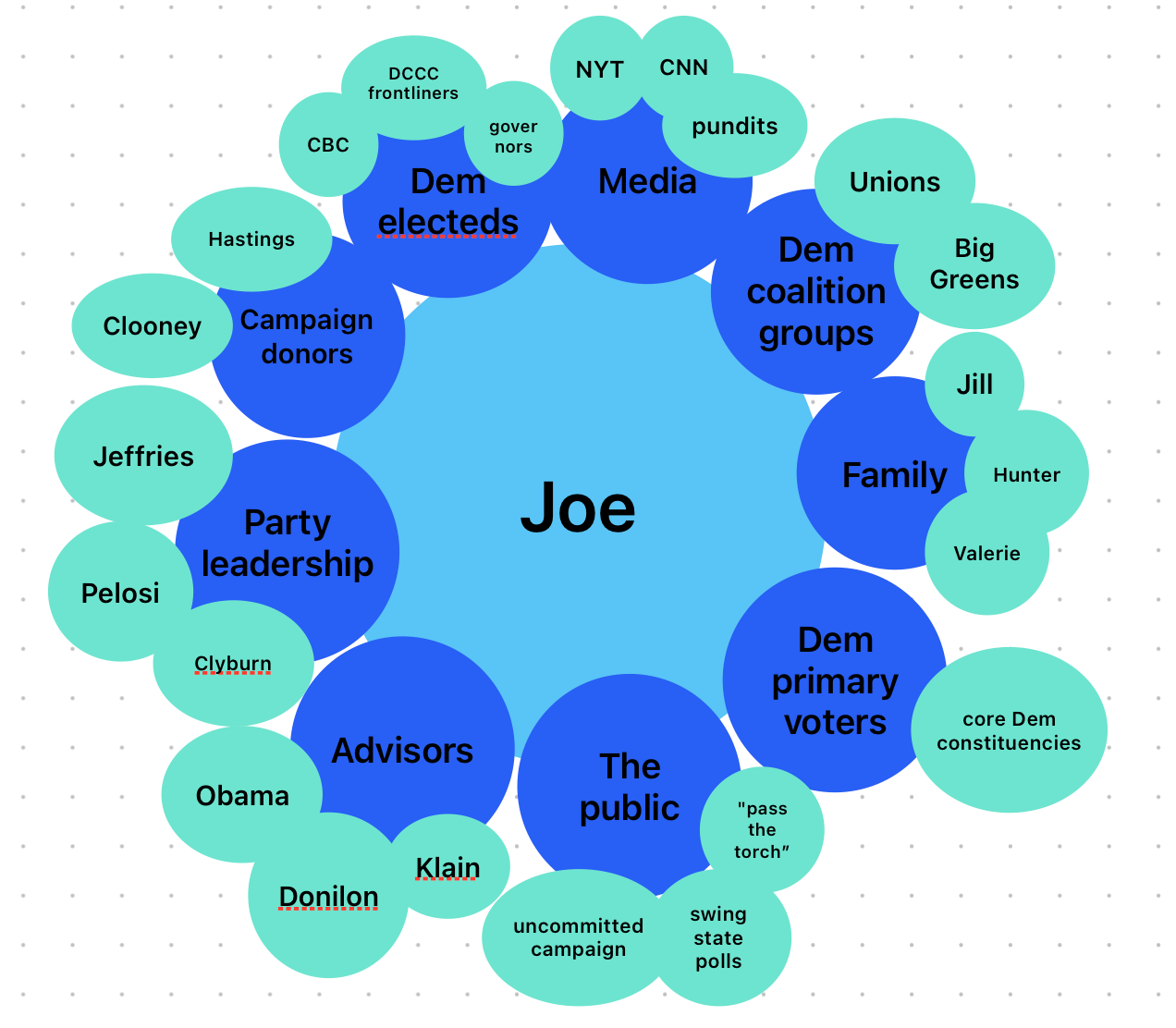

In order to understand how Biden might get there, let’s power map the president. Power mapping is a tool that campaigners use to establish who has influence over a decision-maker. Once we know the players, we can develop campaigns that exert leverage most strategically.

Here’s a rough power map of the circles of influence around the president.

One of the biggest errors that I see in punditry is this idea that some nebulous actor — “the party” — should intervene to force Biden out. As the map makes clear, power is not a monolith, meaning campaigners have many potential points of leverage. These are both the points where a decision-maker derives power, and the points where change-makers can exert influence.

So let’s get even more granular.

This map is obviously not exhaustive, but I hope it dispels the myth of the party as a uniform actor. (In the best version of this exercise, you get even more specific, identifying the actual humans with the power at each institution. To borrow from radical labor organizer Utah Phillips, the people who comprise this constellation of power have both names and addresses.)

We’re very much in the middle of a campaign to influence Biden to make the decision to drop out. No one is coordinating it, but it’s clear it’s happening:

The public has expressed reservations about Biden’s candidacy for years now, in the form of historically high disapproval ratings

The media, in the aftermath of Biden’s horrific debate, has taken the gloves off in their coverage of the president. The editors or editorial boards of the New York Times, the Atlantic, the New Yorker, the Boston Globe, the Atlanta Constitution-Journal, and more have called on Biden to drop out. Twitter is out for blood.

Campaign donors have also been pulling their support in an effort to sway the president. “No one is picking up the phone” to donate, reads one headline from CNBC.

As David Dayen at The American Prospect points out, the Biden campaign has been spinning this erosion of support as an elite phenomenon, the neurosis of an anxious, overeducated class and not the will of the core constituencies who will ultimately vote in November. This line is misleading — a heavy 47% of Democratic voters said Biden should be replaced after the debate — but it speaks to a real phenomenon: the absence of mass defections from the base of support where Biden derives his power.

This is where Biden’s psychological profile matters. Because a power map that weighs all points of leverage as equal won’t prove effective. Losing billionaire Reed Hastings and the New York Times opinion section, as we’ve seen, is not the same as losing the Congressional Black Caucus or a member-led union.

Because Biden views himself as stuttering Scranton Joe, perennial underdog, he’s brushing aside calls for him to drop from the “elite” forces that, in his view, have always underestimated him. During the 2020 primary, the New York Times editorial board ended up co-endorsing Amy Klobuchar and Elizabeth Warren, but not before a fairly combative interview with then-candidate Biden (Time is a flat circle: the headline for the interview is ”Joe Biden Says Age Is Just a Number”). Biden was also not the choice of the Democratic donor class in the 2019 primary, significantly under-raising his opponents. Even among early 2020 primary voters, Biden took a shellacking, finishing 4th in Iowa and 5th in New Hampshire (“a trouncing,” as Politico described it).

What changed? A phone call. Jim Clyburn, then the third-ranking Democrat in the House, endorsed Biden on the eve of the South Carolina primary. Biden won with more than twice the vote total of his closest rival, Bernie Sanders. As contemporaneous reporting had it, this was also the moment where Obama got involved for Biden, after staying out of the contentious primary for months. The former president reportedly influenced Pete Buttigieg to endorse Biden and pressured Mike Bloomberg to drop out, clearing the moderate lane for Biden to romp to victory over the progressives split between Sanders and Warren.

Now we can return to the two pathways to getting Biden to drop: influencing those closest to him or forcing his hand by removing the sources of his legitimacy. Neither are particularly likely in my estimate.

The first is the call from inside the house. There are only a handful of people in the world who have direct influence over Biden’s decision to not seek another term for an office that he has been pursuing for his entire career. These are Obama, who tipped the scales for him in 2020, Clyburn, who credibly represents the powerful constituency of Black voters who power Democratic politics, and his family, who have endured immense tragedy together.

Jill Biden says her husband is “all in.” Hunter Biden urged his father to resist calls to drop. Obama publicly circled the wagons around Biden after the shaky debate. After floating potential support for Kamala Harris and appearing open to a ‘mini-primary’ to replace the president, Clyburn, a co-chair of the Biden re-election campaign, has made clear that he’s “ridin’ with Biden.” As long as this inner circle — the people who have helped him back up when he’s down — holds, so will the president.

The other pathway is to remove the pillars of support that are holding up the president’s legitimacy. Again, not all circles of influence in the power map are created equal. This is why it’s helpful to pair the power map with another tool, the pillars of support. (Assiduous readers of this blog will remember this tool from a previous post in which I analyzed the right’s campaign to remove Harvard President Claudine Gay from her post.)

I think there are three major categories of support here: the elite, like the media with the power to shape the narrative surrounding Biden as beleaguered and the donors who resource his campaign; the party insofar as it exists outside of Biden’s influence, including the red-to-blue swing seat candidates who need to distance themselves from Biden as he drags them down and the Congressional leadership who rely on the trust of their members; and the public that will ultimately decide Biden’s fate.

As I see it, Biden has lost the least influential (insofar as they can influence *the man himself*) pillars of support among the elite. While it looked like the dam was breaking when DCCC frontliner Angie Craig called on Biden to step down over the weekend, no other swing candidate has joined her. Red state senators like Sherrod Brown have hemmed and hawed about the president without exerting real pressure. Party leadership, from Hakeem Jeffries to Chuck Schumer, seem incapable of stanching the flood of leaks from their members, which adds to the air of uncertainty surrounding Biden without really pressuring him.

But this is the kicker: on July 2nd, at the height of Democratic handwringing after Biden’s debate performance, polling from Reuters/Ipsos showed 32% of Democrats supporting an end to his presidential bid. In other words, a supermajority of Democratic voters, at the nadir of his campaign, still wanted Biden as the nominee.

This is Biden’s strongest claim to legitimacy, and unless key constituencies or leaders that represent them (think Black churches and union locals) defect, Biden will keep resisting calls to end his run.

This is the simple reason I think Joe Biden will remain his party’s nominee: the core base of his support has held firm. This is by no means enough to win the presidency in November, but it is enough to claim legitimacy as the Democratic nominee. It’s also same reason that Donald Trump continues his iron chokehold over the Republican Party, even after the elite defections over the last eight years.

This is my interpretation of the pieces on the chess board as it stands now. Things are fluid: since drafting this post, the Communication Workers of America has re-affirmed its support of the president, Pelosi suggested on Morning Joe that Biden’s mind is somehow not actually made up, and New York Dems are panicking over polls that show the deep blue bastion growing more and more purple. Another stumble from the president would absolutely rearrange these chess pieces. Further cracks in the pillars will appear.

My fear is that we’re headed towards a scenario in which the president runs out the clock before the convention while he continues to lose support on the edges, without enough cracks in his core supporters, those with legitimate claim to “the public,” to force him out. He then enters election season seriously weakened, after facing an onslaught of ads questioning his fitness without a younger man’s ability to combat them.

For all that, he might still win. But it’s an enormous, cynical gamble. The reward (a weakened Democrat serves another four years) pales in comparison to the risk (losing the “soul of the nation,” in the president’s words). I used to think that Trump had a hard ceiling of public support of less than half the country: he earned 46% of the popular vote in both 2016 and 2020. If Trump enters 2025 with a popular mandate from the country, which is looking increasingly likely, the blame will fall on the shoulders of one person: Joe Biden

Burn After Reading

I’m in the Nation’s print edition this month arguing that young people should continue to contest for territory inside the Democratic Party’s big tent. There’s a big power vacuum in the party. We should fill it.

Ultimately, politics is a negotiation. Like any negotiation, it pits people with different kinds of power against each other. This is what I did not understand in 2012. My power does not come from standing outside the tent, but from organizing to bring more progressives into it.